The first time I saw a punk drummer share a stage with a border journalist and a historian of caste, I laughed out loud. Not because it was absurd, but because it worked. Somehow their voices braided together, and by the end of the session people were nodding in unison as though they’d always belonged in the same conversation.

That was Dallas, 2018. I’d just helped bring the Hay Festival to my hometown, working out of the back office of The Wild Detectives, the bookshop I co-run. At the time, friends would ask why I was sinking months of unpaid hours into something that looked, from the outside, like controlled chaos: spreadsheets, permits, constant emails. I never had a crisp answer. Looking back, I realize it wasn’t about the work itself. It was about creating a room—literal rooms—where people could still look one another in the eye.

Why a Festival Feels Different

We live in an age where presence is negotiable. You can log in, mute, disappear, and no one will know. That convenience is seductive, but it’s also corrosive. It eats away at the kinds of encounters that change us—the accidental ones, the awkward ones, the ones you can’t click away from.

Festivals resist that erosion. They drag you out of your timelines and sit you in a chair across from someone with a story to tell. You’re not scrolling past their words—you’re breathing them in, sentence by sentence, with two hundred other people holding their breath beside you.

I learned this lesson years ago when I moved abroad. My command of the local language was shaky at best. I went to lectures and readings, said almost nothing, and let silence do the work for me. What I discovered in that silence was a new way of listening—slow, deliberate, porous. Festivals offer that same discipline. They teach us to be students of attention.

A Generational Rediscovery

My grandparents never questioned the need to gather. Their lives revolved around Sunday markets, smoky bars, or neighborhood dances. Connection was a physical act, inseparable from place. Then came the web, which trained us to believe we could live untethered, stitched together by screens alone.

And yet, watch the faces at a modern festival: teenagers scribbling notes, twenty-somethings waiting an hour to hear a poet, strangers leaning together over food trucks. There’s a hunger there. They know there’s no download button for laughter in a crowded hall or for the hush that falls when a story lands.

The Other Side of Joy

Of course, festivals also sparkle. They hum with music, street food, tote bags heavy with books. But underneath that joy runs a deeper current: restlessness. Every festival is powered by questions—about justice, memory, art, belonging—that don’t have easy answers.

That’s why organizing one can feel indulgent, even reckless, in dark times. While wars burn, democracies wobble, and borders tighten, why pour energy into panels and concerts? The answer, I think, is because of those very crises. A festival doesn’t solve them, but it refuses to let conversation die.

When It Gets Hard

This past year was one of the hardest. Funding thinned, bureaucracy thickened, and the smallest details—flyers, permits, schedules—seemed to trip over invisible wires. More troubling still was the hesitation of some invited guests. In a year when arrests, deportations, and surveillance filled the news, crossing into the U.S. felt risky. I respected their caution. To step onto that plane requires more than a passport; it requires trust.

And that is what makes the people who do show up so extraordinary. Their presence is never automatic. It’s a conscious act, a small declaration that gathering still matters.

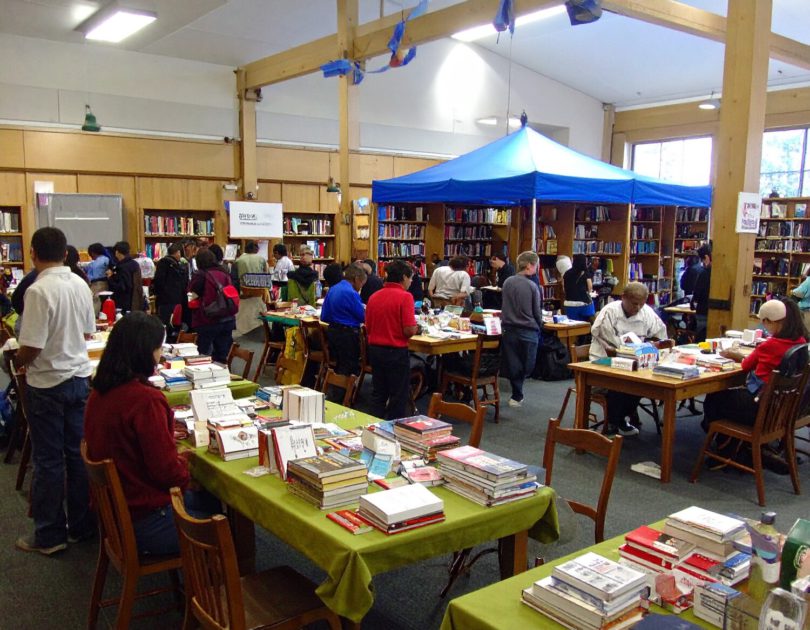

Walking Through the Festival

If you want to see what I mean, picture this: sun filtering through Dallas trees, people drifting between tents and theaters, notebooks tucked under their arms. A woman scribbles furious notes during a lecture on migration. A teenager asks a trembling question at the mic. Strangers argue in the beer garden and end up laughing by the second round.

And then, somehow, a punk drummer is standing alongside a border reporter and a scholar of caste, and the crowd is listening as though their lives depend on it. For a moment, they do.

Why I Keep Believing

That’s why I still believe in festivals. Not because they’re perfect, but because they remind us of muscles we’re in danger of forgetting: how to listen, how to sit with curiosity, how to belong in a room together.

A festival isn’t an escape from reality. It’s rehearsal. A rehearsal for the society we still hope to build—messy, attentive, full of questions, and alive with the possibility that someone else’s story might alter the way we see the world.